Somebody else might walk by without looking at the painfully thin crackhead curled on the sidewalk in the fetal position. Or nudge her with a foot.

Not Deon Joseph.

This muscular black man with arms thick as hams leans over and gently shakes the woman's bony shoulder. He wants to make contact, ensure that she is still breathing.

"How you doing today?"

She curses him, still very much alive.

"Have a good day, ma'am," he replies, moving on down the line of dazed people and overstuffed shopping carts outside the Union Rescue Mission.

It's just another day in the life of a man shopkeepers and residents of the nation's last true Skid Row call the "Sheriff of Skidberry."

Joseph is senior lead officer for the Los Angeles Police Department, and Skid Row has been his beat for the past 17 years. He prefers foot patrol; it is more intimate. Despite the open drug dealing, piles of trash and omnipresent aroma of urine, feces and burning crack and weed, he has found a community here. These are his people.

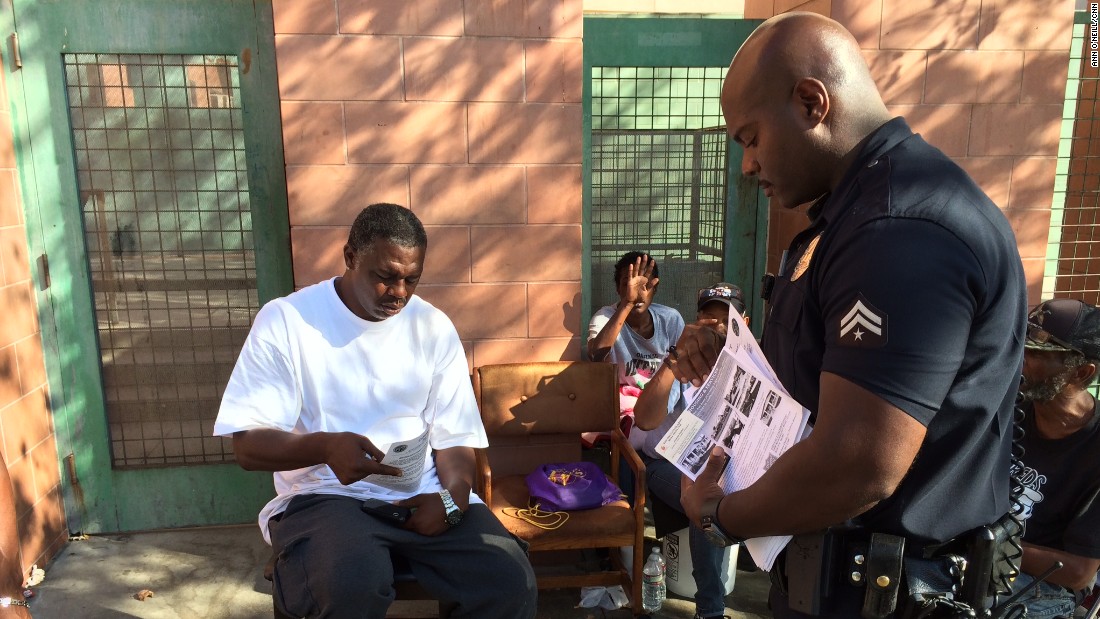

He used to make a lot of arrests, but these days he spends most of his time just talking to people and handing out donated hygiene kits -- toothpaste, soap, deodorant, lotion and shaving cream -- and fliers that explain how to apply for housing vouchers. He leads self-defense classes for homeless women, events he calls "Ladies' Night." He tweets crime prevention tips and offers up anecdotes on Facebook.

He gives out his email address and cell phone number. And then he returns the calls.

And so, he knows nearly everybody -- The Hurricane, Bow Leg, Slow Bucket, Thick 'n' Juicy -- and they know him, too. Some like him, some don't. Most respect him. Some say he's their angel watching over them.

Nearly two decades on some of the nation's poorest, nastiest streets haven't stripped this beat cop of his humanity. He sports a shiny bald pate and kind, expressive eyes. But should the situation call for it, he can turn fierce and scary-looking in a heartbeat.

He is not jaded or cynical, and he doesn't view the world as LAPD blue against everybody else. He is a man of deep, abiding Christian faith, and he considers Skid Row his mission in life. He says he wouldn't dream of working anywhere else.

These are tense times for police and the policed. Everybody's talking about white cops shooting black kids; hundreds show up in small towns and big cities for "Hands Up, Don't Shoot" protests.

Joseph has never fired his gun and hopes he never has to.

In the one-square mile marked by a mural that announces "Skid Row, pop. Too Many," he is a walking, talking public service announcement for the upside of community-based policing.

When homeless addicts call him by his first name, Officer Joseph doesn't feel dissed. He's honored.

"I feel respect when they call me by my first name," he explains, "and I show them respect by calling them sir or ma'am."

In this neighborhood, 2,000 people sleep on the streets at night, by Joseph's estimate. He's seeing a lot of new faces lately as it gets harder legally to commit somebody to mental health facilities, while the prisons and jails are letting inmates out early to ease overcrowding. With nowhere else to go, many head to Skid Row, he says.

Officer Deon Joseph nudged the woman on the left to make sure she was alive.

What happens when 50,000 people move next door to Skid Row?

The dumping ground becomes hot property. And solving homelessness becomes a priority.

The next few years could bring big changes. But Joseph and others say Skid Row doesn't need any more handouts. It has plenty of food and clothing. What Skid Row needs, they say, is affordable housing -- and lots of it.

As much as they'd like to, city leaders can't undo a century of bad urban policy overnight. But there are calls from Mayor Eric Garcetti and other leaders to end homelessness, especially on Skid Row, by 2015. These are the same words Joseph heard from their predecessors a decade ago. Little happened then, and even as 2015 begins, the deadline has been officially pushed back to 2016.

Joseph believes it's time to stop playing politics with Skid Row. The stakes -- literally life and death -- are too high.

"I believe the extremes of both ideologies are what created Skid Row," Joseph says. "By that, I mean the extreme right believes in NIMBYism -- not in my back yard. We'll shove all our problems into downtown LA and come down once a month and throw food and clothes at them and feel good about ourselves.

"And then the extreme left truly believes that because they're poor, black, Hispanic, whatever, because they're of poorer socioeconomic status, that we as law enforcement should just leave them alone. They really believe we should be hands off. And those two ideologies created what we're dealing with on Skid Row."

Seventeen years have shown him that Skid Row isn't going anywhere. "But don't build another one."

Sliding down The Nickel

L.A.'s Skid Row is the undisputed Homeless Capital of the United States and just a short stroll from the power chambers of City Hall and the city's gleaming office towers, trendy bistros and overpriced residential lofts.

To get from the halls of glitz to the corner of grit and despair, just follow Fifth Street. Start at the fancy Biltmore Hotel, scene of many a political victory speech. Cross the park over to Broadway, which is getting a facelift of planters and lights; and then past Spring, which is clogged with hipsters. Once you hit Los Angeles Street, you've arrived in Skid Row.

The trek is known as "sliding down The Nickel." On foot, it takes 15 minutes, tops. But if you use the term metaphorically, the slide can consume a lifetime and land you in a pauper's grave.

I asked Joseph to show me his Skid Row and accompanied him on patrol in mid-September. I shadowed him on a Saturday, a weekday and the following Saturday night. Each tour had a different vibe. The day shifts seemed more like a Fellini street festival. But at night, oh, what an edge! Skid Row turns scary after dark. It was not a good place to be a stranger, especially a well-dressed, well-fed, blond female stranger.

Joseph's beat includes some of Skid Row's meanest streets.

Those who are missing limbs get around on wheelchairs and jerry-rigged devices made from wagons, tricycles and carts.

While I watched, a woman sitting on the pavement shot heroin between her toes and then slathered her feet with moisturizer from a donated hygiene kit. She was oblivious to my presence and pretty much everything else.

Skid Row appears on no official city map. The boundaries were plotted in a 2006 court decision: Third Street on the north, Seventh Street on the south, Alameda Street to the east and Main Street to the west.

Joseph's beat includes two of Skid Row's worst blocks: San Pedro and San Julian streets, between Fifth and Sixth, where the concentration of missions and other services draws the most desperate.

"You cannot separate the blight and crap that's out here from death," Joseph says as we walk past one homeless person after another, huddled in mounds of donated clothes piled into shopping carts.

Some find a measure of privacy in tents they construct by draping tarps over shopping carts. Once under cover, a person can drink, drug, sleep, screw and even die in peace.

"One time I saw a guy sitting on a pile of trash and I saw a hand, a white hand. I thought it was a mannequin," Joseph recalls. "It wasn't a mannequin. It was a dead woman. He didn't realize he was sitting on top of a dead woman, eating donated food."

I think about this story on another day, while we're on patrol in his car. A hand rises up from under one of those ubiquitous blue tarps. It's more of a salute than a wave. A woman, recognizing Joseph, is sending up a signal: "It's all good."

It isn't always.

Joseph tells the story of a 6-foot-4 addict who arrived on Skid Row 275 pounds. A year or so later, Joseph barely recognized the man when he nearly tripped over him on the sidewalk. He was down to 85 pounds.

"I thought he was dead," Joseph said. "I pulled his sleeve and maggots and flies came out. He'd been lying there for a while. There were dozens of people around and nobody called an ambulance for him, nobody.

"I looked at this guy and I said, 'Hey, are you OK?' And he says, 'Joseph, just leave me be. Let me die. I got two days left on this Earth, so just let me die right here.'

"And I said 'Uh-uh, you're not dying on my block.' I called an ambulance for him. They took him to the hospital. He died five days later, but at least he died with some damn dignity."

It's hard to tell what's trash here and what isn't, who's living and who's dying. Joseph points to what looks like mounds of dirty laundry, piled up on the sidewalk.

"This is where people's good intentions go in Skid Row," he says. "People donate clothes, and they're thrown in the street. People urinate, defecate in the street. Nobody cleans it up.

"It creates a really toxic environment. Now when I say 'toxic,' we have staph, we have MRSA, we have HIV, we have tuberculosis, we have all these things. It's like a giant petri dish."

I stop to feed the parking meter with a credit card. A breeze is blowing, and I brush my hair back from my face.

"See what you did there?" says Joseph's partner, Danny Reedy. "You just touched your face. We don't do that after we touch things here."

Joseph's partner, Danny Reedy, warned a reporter about the unsanitary conditions on Skid Row.

L.A.'s is essentially the last true Skid Row in the nation. It has the highest concentration of homeless in the country, according to a recent report by an ad hoc committee calling itself Plan for Hope.

San Francisco has the Tenderloin District, but it is tiny by comparison. As mayor, Gavin Newsom led an aggressive campaign to find subsidized housing and reunite homeless residents with their families. Seattle's homeless have been pushed to the grassy hills overlooking Interstate 5; its former Skid Row streets are dotted with trendy bistros and galleries. And in New York, The Bowery has become so gentrified that it now boasts a Whole Foods Market.

"Gentrification" is a dirty word along Skid Row. But it's inevitable. It's already happening in the blocks nearby, pushing back on Skid Row's Main Street boundary.

Skid Row has its own economic engine -- and it's not crack cocaine or the handmade soy soaps sold in the gift shop of the Downtown Women's Center. Some $54 million is pumped each year into Skid Row's 107 charities that provide services to the homeless, according to a report released in September by a group calling itself "Plan for Hope."

By comparison, the city of Los Angeles earmarked the same amount -- $54 million -- for the arts in its 2014 budget.

Developer Tom Gilmore, who converted old bank and office buildings into residential lofts, sparking the downtown development renaissance, says Los Angeles is "the last city in America to develop its urban center." It has taken two decades to reverse the exodus to the suburbs and bring people back downtown.

Skid Row didn't spring up by accident, he adds. It's the result of a century of neglect and poor urban policy. A decision in the 1970s to centralize services for the poor on Skid Row turned it into a dumping ground for every social ill imaginable.

Gilmore thinks the city has arrived at "a golden moment" to do something about homelessness.

"There's a new consciousness that is extremely sensitive to the needs of the homeless," Gilmore said. "Does that mean they accept the notion of Skid Row? No, no, no because Skid Row is a travesty as a construct. It's a toxic environment for the homeless."

"Nobody is going to raise up from there," he says with a shake of his head. "It has to be unwound because it's this Gordian knot of social neglect."

As someone who works Skid Row's streets every weekend, Joseph agrees.

"Skid Row is a toxic petri dish that thwarts any form of recovery," he says. "We have beer barons selling singles for $2, right outside AA meetings."

He has arrested one of the more notorious beer barons several times, but the man usually returns after spending just a few hours in jail. Even an injunction didn't stop him, and now he's threatening to sue Joseph, alleging "police harassment."

Follow any conversation about Skid Row long enough, and it always comes down to the need for more affordable housing. This is especially difficult in Los Angeles, which is among the most expensive housing markets in the nation. It is not unusual for working people to spend half their income putting a roof over their heads.

Skid Row is just a few short blocks from the gleaming office towers of downtown Los Angeles.

Meanwhile, private, for-profit development of Skid Row is inevitable, Gilmore says. But he is quick to add that the homeless population isn't going anywhere -- not as long as the missions and other services for the poor are located there.

It's a big point on which the developer and the beat cop can agree. The services can't be dismantled, but they can and should be decentralized. Other parts of the city, they say, need to step up and share responsibility.

Nationally, chronic homelessness is down slightly more than 20%, according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

But not on Skid Row. Here, the numbers are going up.

How much? The answer should come soon. The last official headcount cited in the Plan for Hope report found about 1,300 people living outdoors in the 50-block area designated as Skid Row. Estimates last summer ranged around 1,500. By December, Joseph's best guess -- and the LAPD's -- was 1,900 to 2,000. He had just finished a weeklong outreach program under the banner of Operation Healthy Streets.

The program has replaced the harsher tactics that included criminalizing outdoor camping and arresting everyone in sight during massive sweeps. Now police work in small groups that include county mental health workers and volunteers. They ask the homeless what they need and refer them to programs and places that can help.

Four times a year, they pressure-wash the sidewalks and haul away the trash -- 3.5 tons of it during a weeklong sweep in the fall. That included 184 needles and syringes, 63 razor blades and seven knives. Sanitation workers hosed urine and feces from hundreds of curbs, corners and building fronts.

Eighty homeless people were treated for scabies, open wounds and other maladies. Twenty-seven were referred to county mental health services. Four were sent to detox.

It is more hands-on than tossing loaves of stale bread and discarded Hello Kitty T-shirts at the homeless.

Downtown loft dweller Betsy Starman is now among the volunteers. Her involvement began in the summer, when she posted to a Facebook group called DTLA about a woman squatting at Fifth and Hill streets.

The woman muttered and clawed at herself, and her skin was covered with sores. She had fashioned a diaper from newspapers. She didn't want anyone's help.

Joseph saw Starman's post and approached the woman with a box of adult diapers. But she didn't want his help, either. There was little he could do for her.

But he and Starman started talking, and she attended a 10-week Citizens Police Academy, graduating in November.

Operation Healthy Streets reflected a big change in direction. Finally, the city, the county and some of downtown L.A.'s 50,000 new residents are working together.

"Deon Joseph was the only one talking about the homeless, the mentally ill, and the addicted that I could hear," Starman said. "We have many who pontificate and pretend they do things and have their photo ops, but Officer Joseph is not like that.

"He's real," she added. "It gave hope to me, and it gave hope to the entire city. It started a movement, and it is still moving. Many of us could not have become involved or had any hope whatsoever without him."

Joseph used to make more arrests: now he also hands out hygeine kits and housing information.

On the second day I shadowed him, Joseph had a trunk-load of hygiene kits in his patrol car. He drove to Gladys Street Park, where people crowded around him, hands outstretched, clamoring for "Swagger!"

It's an especially potent deodorant and body spray by Right Guard.

But Swagger can only cover up the inevitable truth for so long. The place smells like old tennis shoes that have been urinated on by 1,000 people with body odor. Since it hardly ever rains, the pungent aroma of urine and excrement never really washes away.

It takes a while to scrub Eau d'Skid Row from your clothes, your hair and your nostrils.

Somehow Joseph has gotten used to it. He wears black rubber gloves everywhere and chews a lot of gum.

He grew up in Long Beach during the Rodney King era, when distrust of the LAPD fueled racial tensions and devastating riots. Like his friends, he was no fan of the po-po. So nobody was more surprised than Joseph himself when he signed up for the Los Angeles Police Academy.

"I needed a job," he says.

As a rookie, Joseph prayed he wouldn't be assigned here. He liked the hip, beachy vibe of Venice, where he trained. But when the permanent postings came out, Joseph wondered whether he had prayed hard enough.

Driving to Skid Row on his first day of work, Joseph cruised up the 110 freeway, glimpsed the gleaming skyline and thought, "Look at that pretty picture. This can't be all bad." He took the downtown exit, relieved to see people on the sidewalks in suits and ties.

And then he crossed Spring Street.

"It was if I tripped and fell into Dante's Inferno. And I couldn't believe how fast it happened. I wasn't prepared for it."

He drove another block. It only got worse.

"The smell, it hits you as soon as you cross Los Angeles Street. I felt nauseous."

Maybe a police station would serve as an anchor of sanity in the middle of this freak show?

"As soon as I got closer to the station, I saw half-naked women running around urinating on the sidewalk, guys urinating on the sidewalk, people smoking crack. I saw a patrol car and two feet away a guy was injecting himself with heroin. Another person was smoking crack and a fight broke out. An officer couldn't stop it.

"And I'm going, 'Oh my God, I've got to get out off these streets and into the station.' In there, it was worse because on the bench we had addicts and dealers and mentally ill individuals. And the mentally ill individuals were yelling all sorts of things."

He had one thing on his mind: "Oh man, I surely gotta escape."

Long before the sun sets, people start lining up outside Skid Row's missions.

That DNA includes regular church attendance and parents who raised 41 foster kids -- 17 of them while he was living at home.

"My mom had a special love for children. I saw her heal those kids," he said.

His parents grew up poor in Louisiana during the Jim Crow era in the South. His great-grandfather was killed by a 16-year-old white kid, Joseph said, simply because he wouldn't get out of the street. The shooter went on to become the sheriff.

Joseph's father was bitter about the injustice and seemed destined to a life of crime. But a man he tried to rob turned out to be a preacher, Joseph recounted.

"Put that gun down, boy," the man said. "You're not going to jail today, but I want to see you in church."

It changed his life. He moved to California, supported his family at first by collecting and recycling cans. He started a construction company and found success. He hired ex-convicts and veterans and treated them well. His mother fed the homeless. They taught their children to help others rather than judge them, and to love and embrace their color and their culture.

Joseph has experienced racism in his lifetime, but not in the same way his father did. When he was younger, a white kid at a burger joint put staples in his meal. Fliers distributed around Skid Row attacked him as an "Uncle Tom."

But when a colleague filed a racial discrimination suit against his sergeant and the LAPD, Joseph took the witness stand and said it wasn't true.

"This is what I have to do," he says of his career on Skid Row. "I can go anywhere in this department. There are 17 divisions. I can go back to Venice, sip on lattes, chase celebrities in Hollywood. I can go anywhere. I can leave at any time. I choose to be here. I want to help these people. It's in my heart to help these people."

Taking inventory

"Helping these people' has gotten complicated, as I learned on my final ride with Deon Joseph.

Years of court battles have determined what cops can and can't do on Skid Row. The days of declaring street camping illegal and making mass arrests are over. No more hook 'em and book 'em. Police can no longer just sweep what looks like junk off the streets. That junk might be somebody's only possessions in the world, the courts have ruled.

It is harder than ever to obtain an involuntary commitment against someone who might be dangerous.

Joseph vented his frustration this past summer in an open letter published in the Downtown News. It's how he caught my eye. Here was an LAPD cop calling out the city for ignoring Skid Row. That was unusual enough. But then he didn't get in trouble with the brass. That was extraordinary.

He called Skid Row "an open air mental asylum." He said the city was on the brink of an epic meltdown, and there wasn't much he, or the LAPD, could do about it.

"When it comes to policing Skid Row, it seems as if my fellow officers and I are keeping our fingers in the cracks of a dam to keep it from breaking," he wrote. "Though many people may not realize it, we are in the throes of a mental health state of emergency."

He said police have to wait until something bad happens before they can do anything.

Donated food and clothes add to the filth and clutter on Skid Row's streets, Joseph says.

Joseph has appeared in several documentaries and starred in a handful of YouTube videos. In the most controversial, he pleads with do-gooders not to simply hand out food and clothes on Skid Row.

It's not that he's anti-charity. Far from it. But bottomless freebies keep people out of the missions and away from services that can actually help them. By donating, well-intended people become part of an enabler economy based on the hustle.

"Nobody ever goes hungry on Skid Row," Joseph says, and it's true, only the deeply addicted get scary-thin. Many of the others could even stand to lose a few pounds. Yet somehow Joseph's message was twisted into "Don't give to the homeless," which is not at all what he meant.

He has an uncanny ability to strike a nerve. He gets into his share of controversies. But he's hard to ignore.

Among his critics is General Jeff Page, with the Los Angeles Community Action Network, a homeless advocacy group. General Jeff, as he's known around Skid Row, is a hip-hop impresario who runs a three-way basketball league in one of Skid Row's parks. He and Joseph used to be friends.

Neither will say what caused the falling out. General Jeff says Joseph is a media hound who steals LACAN's ideas and takes credit for them. He calls him a phony and points out that the streets on Joseph's foot beat are among the city's messiest.

Joseph refers to his critics as "my detractors" and won't get in a tit-for-tat with them. It all sounds like a high school sandlot beef.

Also on his personal list of "detractors" is the ACLU. The civil rights lawyers objected in court to how the LAPD was handling Skid Row with massive sweeps and arrests.

Although no longer a fan of the tactic, Joseph says it got results.

"We used small laws to stop bigger things from happening," he said. "It worked. The tents came down. They were allowed to sleep until 9 o'clock. There wasn't a lot of garbage on the sidewalk. They didn't have a lot of shopping carts to hide behind. They couldn't sit on the sidewalk and get comfortable in their own destruction."

He says the numbers back him up. When the city was carrying out sweeps and arresting people, crime on Skid Row dropped 40%. In 2005, 93 people died in Skid Row's shelters, and 18 on the streets. But by 2009, only five of the 63 deaths occurred on the streets.

The ACLU won a second decision in 2011 that set further limits on what police could do. The suit alleged that the LAPD was harassing the people of Skid Row by seizing their tents and other property.

"They were able to sell that we were hassling people," Joseph says. "If I wasn't a cop, I would have believed it, too."

The courts have ruled that on Skid Row, a tent is a homeless person's castle; what might appear to be trash is actually personal property.

It's what cut short our final tour of Skid Row.

Each time he makes an arrest, Joseph has to consider whether it's worth the time it takes him off the street.

Yet we didn't last half an hour on the streets. Joseph had to weigh whether to make an arrest or keep going. An arrest entails paperwork and hours of inventory. If nobody is bleeding, is it really worth it?

A thin black man with droopy jeans was spreading perfume bottles, combs, mirrors and makeup on a blanket on the sidewalk. It's considered illegal vending. He had several cartons with him, and two overflowing shopping carts.

The crime might seem petty to an outsider, Joseph explained, but the guy keeps coming back, each time with more trinkets. It's like he's laying down a challenge, seeing how far he can take it. Joseph decided he'd seen enough.

He ran the man's name through the computer in his patrol car and found two arrest warrants out of Long Beach. The man was wanted for assault.

Bingo!

He placed the man under arrest, and Joseph and two other officers hauled his trinkets back to the station and spent the next four hours cataloging the man's personal possessions -- putting labels and tags on each perfume bottle, hair clip and tube of mascara.

Joseph's shift came to a close before he could return to the streets. He gathered up his gym bag and walked to his car, parked in a lot behind the station. On the way out, he spotted an inebriated man lurching along Wall Street. The man stopped, unzipped and proceeded to relieve himself.

"Please sir," Joseph says, "do not urinate on my police station."

Where the daily battle is so huge, it's the little things that matter.

No comments:

Post a Comment